Mosquito-borne diseases pose a significant global health threat, resulting in over one million deaths and infecting up to 700 million people annually. A new study led by University of Florida researchers reveals a disturbing trend that could worsen an already precarious situation.

Published in PLOS Climate, the study’s findings reveal that climate change is causing the mosquito’s potential geographic range to expand and shift. An adaptable type of mosquito, known as a ‘container breeder’ for its ability to breed and lay eggs in urban areas, may thrive in a changing world. This, coupled with globalization, raises the risk of introducing new mosquitoes and pathogens. Areas previously untouched by these insects may now be infiltrated, while regions that had seen dwindling disease may witness a resurgence.

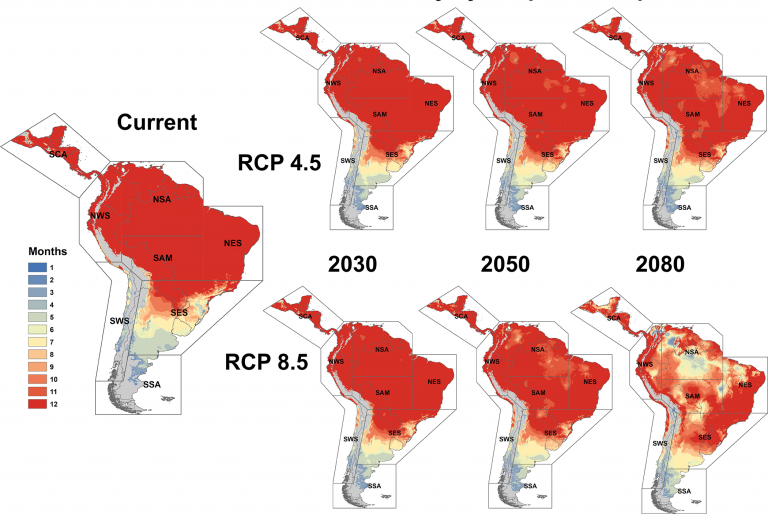

Of particular concern is the potential introduction of the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Originally a key factor for malaria spread in the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East, which has spread to parts of Africa, this mosquito has evolved into an urban-adapted container breeder, unlike most malaria-spreading mosquitoes. The authors’ maps indicate that conditions in many parts of the Americas are already suitable for its establishment.

The study was led by UF geographer Sadie Ryan and postdoctoral associate Catherine Lippi, experts in vector-borne diseases and transmission and members of UF’s Emerging Pathogens Institute (opens in new tab).

“It is important to think about the risk of invasion and spread, in addition to quantifying the potential for climate change to shift and alter the risk of existing mosquito-pathogen combinations,” said Ryan.

The researchers also found that the mosquito season will lengthen in many places in the Americas as the climate continues to change, enabling extended breeding periods and an increase in mosquito-borne disease outbreaks. The research shows that regions once considered safe from infections may soon become vulnerable.

“This study reveals the potential impact of multiple arboviral diseases plus potential malaria spread with a novel vector introduction into the Americas,” said Ryan. “By mapping this in a regional context, we can illustrate which sub-regions and individual countries will face increased risks, and by which mosquito-disease combinations.”

The researchers noted a gap in detailed assessments of the far-reaching impacts of climate change on global public health. The need for a more comprehensive understanding motivated their examination of the intersection of climate change, demographic shifts, and disease transmission in Central and South America.

“It is important to communicate these types of assessments to decision-makers, and by providing comprehensive open research, output maps, and data, they can utilize and implement their own assessments,” said Lippi.

Using inventive geospatial analyses of temperature-driven disease transmission risk combined with climate and demographic projections aligned to the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the researchers highlight the projected risk in the Southwestern South America sub-region. The projections indicate a stark rise in the temperature-driven risk of dengue and Zika transmissions under future climatic scenarios. Brazil faces the most substantial population risk for the introduction of arboviral diseases and malaria.

As the planet warms, the synergy between climate change, population dynamics, and mosquito-borne diseases demands attention. The study underscores the necessity of factoring demographic shifts and climate models into future disease risk assessments, offering insights for shaping effective public health strategies.

The study’s findings share a roadmap for future research and policy development to address the changing landscape of mosquito-borne disease transmission risk. They underscore the need for governments and policymakers worldwide to proactively address the ever-evolving challenges posed by climate change on mosquito-borne diseases.